Uncertainty over the future taxation of diesel cars could bring forward the ‘tipping point’ where electric cars become more cost-effective for fleets than conventional vehicles.

While announcements from manufacturers and the Government have created confusion in mainstream media, targets for average CO2 emissions less than four years away are driving the launch of more electric cars.

At the same time, improvements in battery chemistry and a reduction in costs are making them more accessible.

As the Government and local authorities tackle local air pollution issues by discouraging use of diesel cars, plug-in cars are the likely alternative.

In July, an announcement by Volvo that it would only produce cars with electrified powertrains from 2019 was widely misunderstood that it would no longer be producing cars with petrol or diesel engines.

But Volvo already offers plug-in hybrid variants in most of its models launched since 2015, and by 2019 it will have renewed its entire line-up.

BMW revealed in August that a new flexible vehicle architecture will enable electrified powertrains on all future models, as well as confirming a pure electric version of the Mini would go into production in 2019 in the UK.

Oliver Zipse, BMW AG management board member for production, said: “Our adaptable production system is innovative and able to react rapidly to changing customer demand. If required, we can increase production of electric drivetrain motor components quickly and efficiently, in line with market developments.”

By 2025, the BMW Group expects EV to account for between 15-25% of global sales.

The market for alternative fuel vehicles, which includes hybrids charged by the internal combustion engine, plug-in hybrids, pure electric cars and hydrogen fuel cell models, continues to grow, taking a record 5.5% share of the UK market in July (4.3% year-to-date).

The previous alternative fuel vehicle (AFV) market share record was set in June 2017 at 4.4%, and if registrations of diesel cars continue to decline, AFV share will grow, even if increases in outright numbers are more modest.

Manufacturers are being compelled along this route by tightening emissions rules, while infrastructure for electric vehicle charging continues to expand.

However, not all carmakers are as vocal about electric alternatives. Mazda, for example, has just reaffirmed its commitment to petrol with announcements about the Skyactive-X engine due to be launched in 2019.

The company says it is “working to perfect the internal combustion engine” which it believes will continue to power the majority of cars for “many years to come” and, therefore, will make “the greatest contribution” to the reduction in CO2 emissions. It concedes that such an outcome would need to be combined with electrification technology, but it remains resolute in its belief in efficient petrol engines.

Manufacturers are shooting for European Union targets for average new car CO2 emissions of 95g/km by 2021 (versus 130g/km in 2015). Low-emission cars must balance high-emission ones, or manufacturers will face fines for exceeding the limits.

They are also being awarded emissions credits for emissions-reducing technology that might not create a significant benefit in official testing, but can be verified to work in independent tests, while vehicles below 50g/km entitle the manufacturer to ‘super credits’, creating a greater offset for higher emission models.

Current incentives for purchasing ultra-low emission cars in the UK are set until October 2017, and offer up to £4,500 off a zero-emission car, and up to £2,500 off the best-performing plug-in hybrids up to a price ceiling of £60,000.

In July, the Government announced an aspiration to stop the sale of new pure petrol or diesel cars in the UK from 2040 and, although the current programme of incentives for plug-in cars is due to finish within months, the car industry believes they need to continue to ensure Government aspirations are met.

SMMT chief executive Mike Hawes said: “The UK Government’s ambition for all new cars and vans to be zero emission capable by 2040 is already known. Industry is working with Government to ensure the right consumer incentives, policies and infrastructure are in place to drive growth in the still very early market for ultra-low emission vehicles in the UK.”

The number of public plug-in vehicle charge points in the UK now exceeds 4,000, while Go Ultra Low, the Government and industry body promoting take-up of plug-in vehicles, predicted earlier this year there would be a total of 100,000 registered and in use by the middle of 2017, although this milestone was reached in May.

Meanwhile Chargemaster, a major EV infrastructure provider in the UK, believes there will be at least a million EVs by 2222, possibly “as much as 1.4 million”.

Chief executive David Martell said: “Over the next five years, a significant number of new models will have a range of more than 200 miles, with a lower purchase price than their earlier vehicles. Consumers will also be able to choose from a larger range of electric vehicles, from manufacturers including Audi, BMW, Ford, Mercedes-Benz, Volkswagen and Volvo, as well as significant new models such as the Jaguar I-Pace and Tesla Model 3.”

Comparing plug-in car costs with diesel

Plug-in hybrids and fully electric vehicles are still only cost-effective in certain roles, but their appeal compared to conventional fuel alternatives continues to grow, as our examples show.

Plug-ins are more suited to urban areas with lower annual mileage than vehicles spending much of their time on motorways.

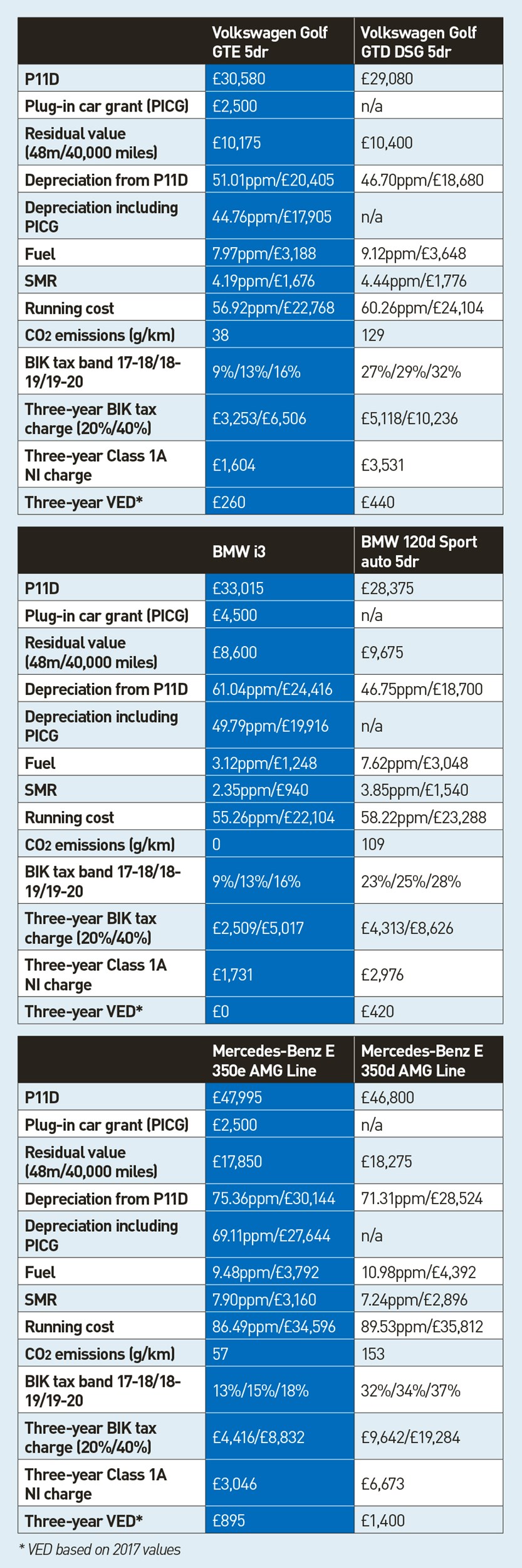

Using running cost figures on the Fleet News website, and taking account of the plug-in car grant to adjust the depreciation cost based on the transaction price, a number of plug-in cars offer lower running costs over four years/40,000 miles.

Also, projected benefit-in-kind (BIK) tax rates over the next three years suggest plug-ins are also more appealing for drivers to minimise tax liability.

The GTD, the Golf’s best-selling derivative in the UK, has similar performance to the plug-in hybrid GTE. But the GTE, which qualifies for a £2,500 grant, is projected to offer a £1,300 saving in running cost over four years, as well as a saving in employers’ National Insurance (NI) contributions of around £1,900 over the next three years – the current extent of NEDC CO2 emissions and BIK tax bands.

The BMW i3 has a P11D value almost £5,000 higher than a BMW 120d Sport auto. However, the effect of a £4,500 plug-in car grant on depreciation, combined with the lower charging costs of a pure electric car compared with fuelling the 1 Series with diesel, as well as lower servicing costs, give the i3 a saving of around £1,100 in running costs over four years/40,000 miles.

NI savings for employers amount to around £1,200 over three years, while there is zero VED to pay in that period compared with £420 for the 120d.

CO2 emissions on the E 350e top 50g/km but it qualifies for the plug-in grant because its range exceeds 20 miles and it costs less than £60,000.

A running cost saving of £1,200 over a similarly specified diesel E 350d over four years/40,000 miles is boosted by a £505 projected advantage in VED, while employers’ NI contributions are £3,600 for the plug-in car. BIK charges for the driver are around half as much as for the diesel over the next three years.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.