The Department for Transport (DfT) has raised concerns on the 10 second rule that is in place for drivers to take back control from automated lane keeping systems (ALKS).

In a new report – ‘Regaining Situational Awareness as a User in Charge’ – published by the DfT, scientists explore driver behavioural responses to transition demands in vehicles with self-driving features engaged.

The study showed mobile phone use in particular had lower disengagement rates, with participants often continuing the activity even when initiating manual driving.

Mobile phone users actually took back manual control of the vehicle more quickly, but the research shows that this did not guarantee a safe transition, as “participants may not have fully understood the driving actions required”.

Current rules dictate a 10 second period between an automated lane keeping systems alert being triggered and drivers needing to take back control.

If the driver doesn't respond within 10 seconds, the vehicle must automatically slow down, put on its hazard lights and eventually stop.

The DfT said the variability with results from the research “raises concerns about the adequacy of the 10-second takeover period”.

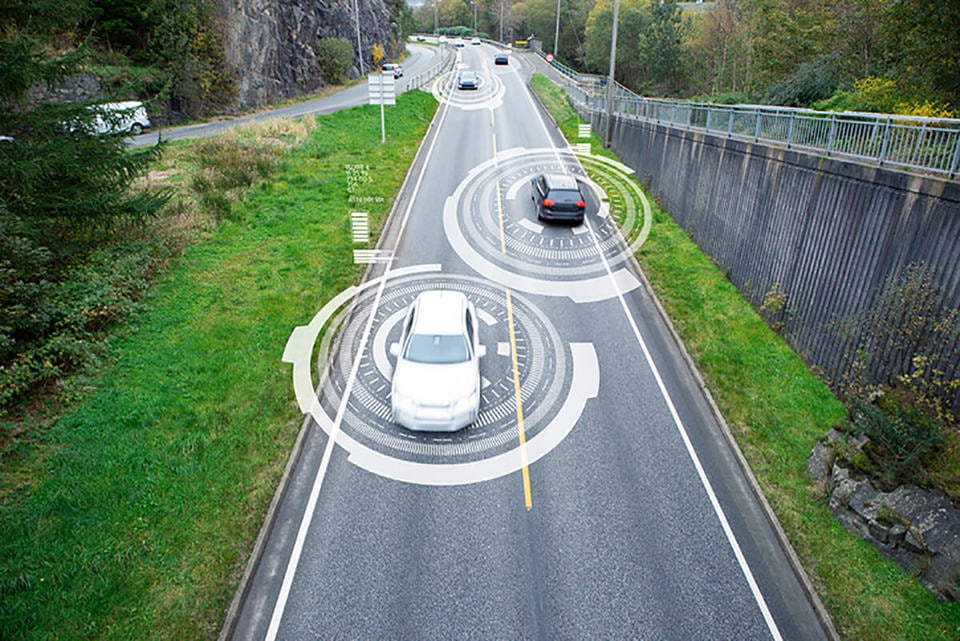

The research is all part of the Government’s work towards putting self-driving vehicles on UK roads by 2026 with its Automated Vehicles (AV) Act.

Many hands-free activities “significantly impair situational awareness”

The DfT report shows that while some non-driving related activities may be safely performed during periods of self-driving in an automated vehicle, many can “significantly impair situational awareness” and delay the transition to manual control, particularly in complex driving scenarios like roadworks.

The DfT said the report: “Draws attention to the need for refined mechanisms to measure situational awareness and establish appropriate thresholds for safe takeovers and the importance of providing clear and specific instructions to drivers in automated vehicles to ensure that they understand how to conduct a safe takeover.

“This includes not just taking control quickly but doing so in a manner that ensures they build sufficient SA to resume manual driving safely.”

The DfT said the variability in participant responses and the influence of environmental factors suggest that further research is necessary to fully understand the nuances of non-driving related activities impacts across different scenarios.

It said: “This ongoing research will be crucial for developing informed policies and enhancing the safety of automated driving systems.”

A significant proportion (67%) of UK drivers have already shared concerns about the prospect of fully autonomous vehicles operating on motorways.

Playing video games while driving

Research specialist Lacuna Agency worked in partnership with University College London and Loughborough University as part of the DfT project, which looked at scenarios where the “user in charge” is engaging in different non-driving related activities.

This includes things like reading a magazine or playing a video game on their smartphone and how these different activities affect situational awareness.

The project used simulators at two locations: University College London and Loughborough University with 97 participants representing the general UK driving population.

The study used two motorway scenarios – roadworks and congestion – designed to simulate conditions that exceed the operational limits of the automated lane keeping systems (ALKS) and trigger planned takeover requests due to speed changes.

The complexities with take-over requests

The DfT project explored the complexities surrounding takeover requests and the role of the ‘driver’, who must be ready to take control when the automated system issues a takeover request.

A takeover request occurs when the automated driving system encounters emergencies or conditions outside its programming. The driver receives the takeover request via visual, auditory, or haptic cues.

These requests can be issued on vehicles with Level 3 autonomous driving features.

There are six levels of autonomous driving.

Level 3 refers to the automated driving function taking over certain driving tasks. However, a driver is still required and must be ready to take control of the vehicle at all times when prompted to intervene by the vehicle.

The need for automated driving systems to hand back control in some emergency scenarios creates an extremely complex challenge that needs to be addressed on the road to introducing new technologies to the UK road network safely.

Some tech-giants like Google’s Waymo are choosing to entirely leap-frog Level 3 in order to remove the complexities involved with handing back control.

Level 5 vehicles do not require a driver to take back control of the vehicle in any driving scenario and would be the “robotaxi” services that companies like Waymo, Uber and Amazon subsidiary Zoox are eager to introduce.

However, other manufacturers like Mercedes, Audi and Toyota are progressing the Level 3 capabilities in their vehicles.

Mercedes was the first automotive company in the world to meet the demanding legal requirements of UN-R157 for a Level 3 system, which was granted by the German Federal Motor Transport Authority (KBA).

Variability with findings raises concerns on 10-second takeover

The ability to safely take over within regulated timeframes was variable.

Although participants were not informed about the 10-second automated lane keeping systems (ALKS) regulation, many attempted to take over quickly.

However, some took longer than 10 seconds, either due to careful disengagement or slower responses.

The DfT said this variability raises concerns about the adequacy of the 10-second takeover period.

The report showed that even simple tasks, such as putting a lid on a pen, can negatively affect a driver’s ability to resume control in a safe and timely manner.

Eye-tracking data showed that participants rarely used mirror checks to build SA after receiving a takeover request. They instead looked at the road, the speedometer and the vehicle’s instrument panel to gain situational awareness.

Certain non-driving related activities, like using a cradled mobile phone, eating popcorn, or doing a wordsearch, significantly delayed response times in roadworks but had a lesser effect in congestion.

Although the difference between the two scenarios was minimal (less than half a second), at motorway speeds, even this delay could be dangerous, covering approximately 15.4 metres in just half a second.

The DfT report concluded: “The variability in participant responses and the influence of environmental factors suggest that further research is necessary to fully understand the nuances of non-driving related activities impact across different scenarios.

“This ongoing research will be crucial for developing informed policies and enhancing the safety of automated driving systems.”

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.