By Glass' car editor Rob Donaldson

There are a number of traditional conversations in the British psyche. For example: the weather, Saturday’s football results and the price of fuel at the pump.

The last subject gets particular airtime as it affects people’s disposable income and can influence car-buying decisions.

For example, when fuel prices rise, larger engine, less efficient cars become unpopular, making them a difficult sell.

A good example of this was the 1970s, when the oil price rose 250% in nine months and dealt a massive blow to ‘gas guzzlers’ around the world, as people could not afford the cost of filling up a car that could only manage 15 miles to the gallon, at best.

There were fuel protests in 2000, when a litre of petrol and diesel reached the dizzy heights of 80 pence. Lorry drivers took action and blockaded refineries, attempting to cut the taxation on fuel.

Increases in pump prices over last two years have again focused the mind and may well have helped towards the uptake of hybrid and electric cars, as people seek to keep running costs down.

However, with the headline cost of oil dropping to under $60 per barrel for Brent Crude, should we expect to pay £1 a litre again as we did in 2009 when it fell to a similar level?

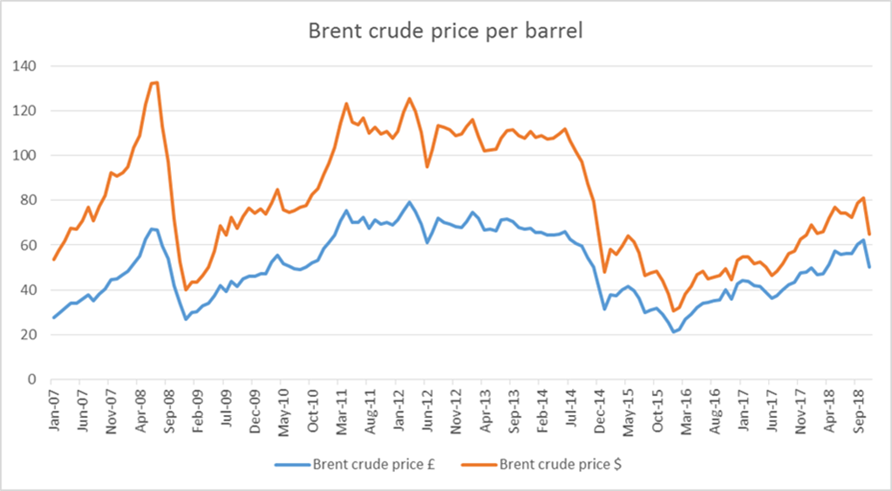

The chart below plots the average price per month of a barrel of Brent Crude oil in £ sterling and US$ over the past 11 years. Brent Crude is the benchmark oil price around the world.

We can see the effect of the commodity bubble which pushed the price to over $130, before the financial crash of 2008 brought a barrel plummeting down to $40 a barrel.

It then recovered over the next 5 years before suffering another big drop, as increased supply pushed prices lower with shale oil coming on stream.

Throughout this period the £/$ exchange rate somewhat softened the impact of the large fluctuations in the UK, but since 2016 and the devaluation of the pound, the price of a litre of fuel is now more sensitive to those international market movements.

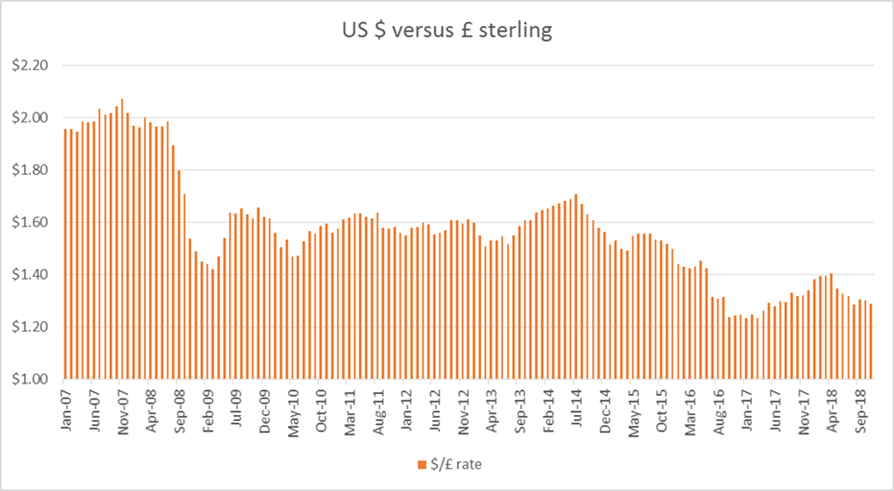

The following chart shows average monthly Pound Sterling versus US Dollar exchange rate decline.

Now let us move on to see the effect of commodity price and exchange rate on the price at the pump.

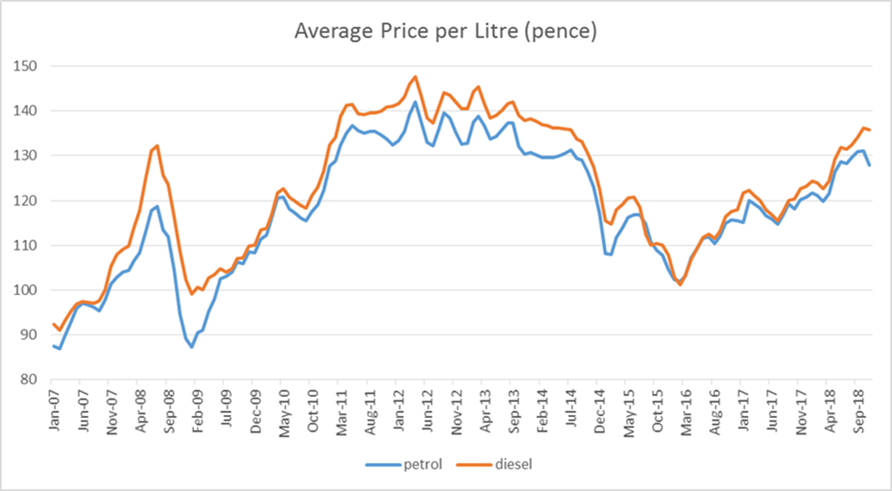

The chart below plots the average price for petrol and diesel per month (petrolprices.com) since January 2007.

It is clearly visible that the price for petrol fluctuated greatly from just under 90 pence in early 2007 to over £1.40 in 2012.

The price dropped again from 2014 to early 2016 but as the exchange rate between US$ and £ narrowed in 2016, we can see the price has risen more sharply, while the headline commodity price per barrel in dollars has not breached US$85.

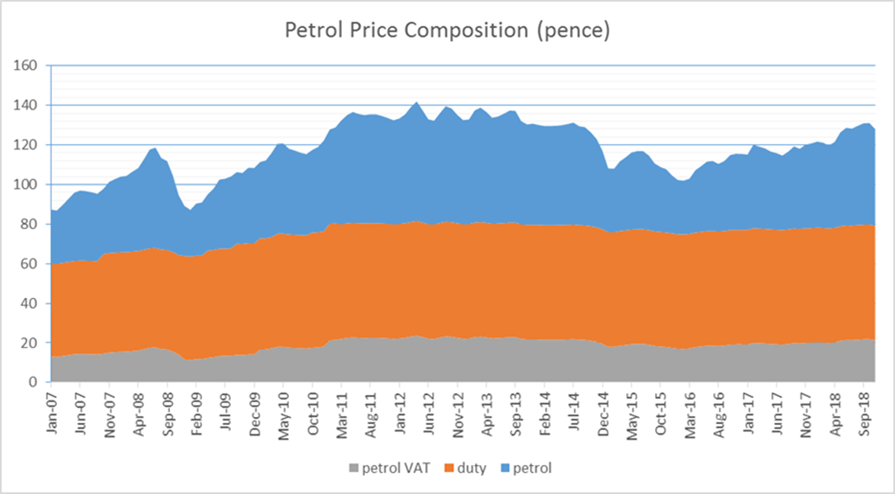

It is widely known that the price of a litre of petrol or diesel in the UK includes duty and tax.

The following chart shows a breakdown of a litre of petrol into its three main pricing components, fuel price, fuel duty and VAT (which is calculated on the total of fuel price AND duty).

Therefore based on the last month of data (November 18) 79 pence of the £1.28 is tax and duty while 49 pence is the fuel cost.

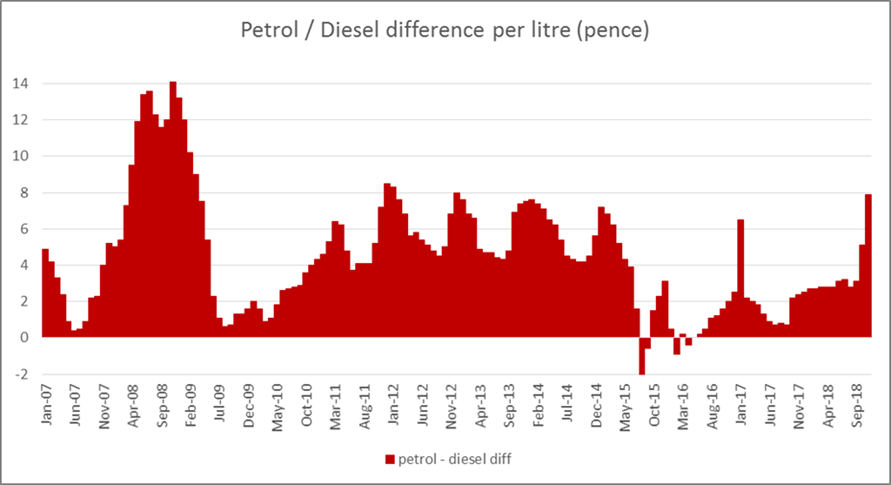

Diesel follows a very similar pattern to the chart above with duty being the same as petrol and VAT is also 20% of total, but what has been the difference between the two fuel types at the pump. The following chart shows the difference per litre.

There are a number of reasons for the fluctuating difference between petrol and diesel including UK and worldwide demand for either fuel type, production quotas, refining capacity, delivery and exchange rates.

In the final chart we plot the cost of a barrel of Brent crude in £ sterling against the price per litre of diesel and petrol minus duty and VAT.

In 2007, the ratio of litre of petrol to a barrel of oil was 100:1, but as the oil price rocketed, the price per litre lagged to a ratio 140:1.

After the financial crash, it went back to 100:1 but then as the barrel price rose back up to £70 and above, the ratio increased again, indicating that the full cost potential did not move onto the price at the pump.

That said, when the barrel price drops below £35, the full reduction does not appear at the pump price.

This will be partly due to other costs involved in the ‘price’ of the fuel which change less, like refining costs, additives, transportation and forecourt reseller margin.

When prices at the pump rise, alternative fuel vehicles (AFVs) become a more compelling proposition for car buyers.

Adversely, if fuel prices drop in the coming months, the pressure on finding alternatives to petrol and diesel are not so concerning and therefore may lead to AFVs being a tougher sell to the customer, especially at the relatively high purchase price that they currently attract.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.