Battery electric vehicles (BEVs) dominate the landscape of zero emission motoring.

Government, manufacturers and suppliers are spending billions of pounds to develop and introduce the technology, with more BEVs being launched and more charge points being installed on a weekly basis.

However, BEVs aren’t the only zero-emission option – and, for some, they aren’t even the best option either.

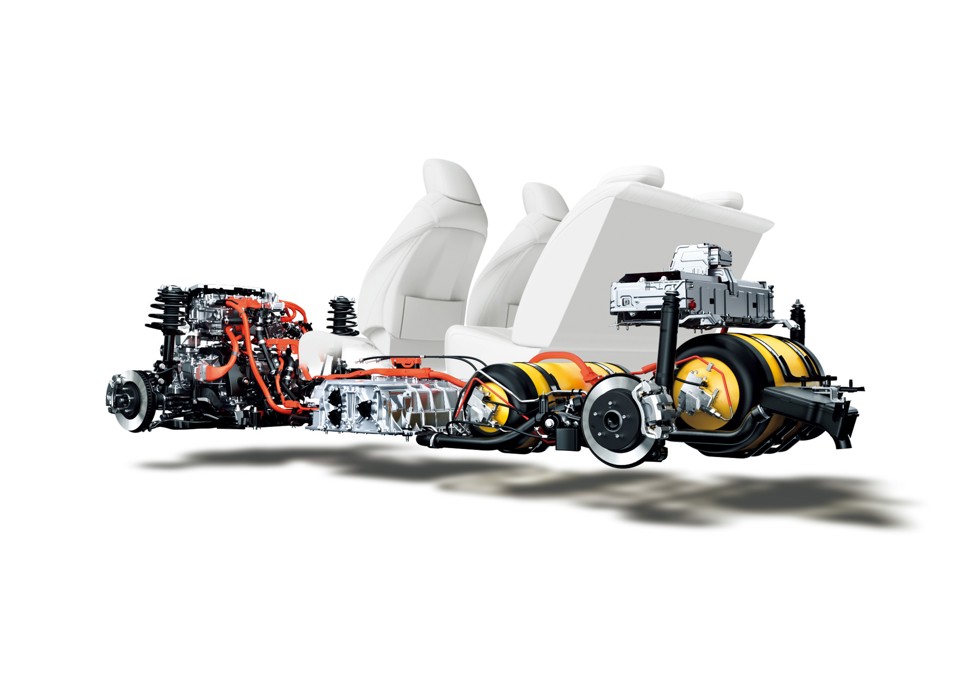

Hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) have been sitting in the background for many years. Hyundai brought the first commercially available model – the ix35 – to market in 2013. But the manufacturer has been developing FCEV systems since 1998 when it opened a dedicated R&D centre.

While the technology is lagging far behind BEVs in terms of vehicle availability and infrastructure, analysts such as KPMG believe they have a significant role to play in the future of road transport.

Like BEVs, the technology produces zero tailpipe emissions but also offers much faster refuelling times: a hydrogen station can deliver around 300 miles of range in five minutes, while it would take a 150kW rapid charger one hour to do the same.

The general opinion among transport industry experts is that FCEV technology works better in larger vehicles, such as lorries and buses, while BEVs will suit the majority of passenger car users.

Current market trends support this. There are just two FCEVs currently available to buy in the UK – the Toyota Mirai and Hyundai Nexo – while the Go Ultra Low campaign says there are 30 BEVs, with this number set to expand rapidly.

Nevertheless, the FCEV’s potential has attracted the attention of the Government as it looks to reduce transport emissions: the Office for Low Emission Vehicles has a £23 million fund to accelerate the take-up of hydrogen vehicles and the roll-out of infrastructure.

One beneficiary is the Liverpool City Region combined authority, which was awarded £6.4m earlier this year for a bus project which will see a new hydrogen refuelling station and potentially up to 25 hydrogen buses on the area’s roads.

Meanwhile, London has placed an order for 20 FCEV buses due to start work next year.

'The larger the vehicle, the more hydrogen makes sense'

“The larger the vehicle, the more hydrogen makes sense,” says Callum Smith, business development officer at ITM Power, which operates seven hydrogen refuelling stations in the UK, with a further six under construction.

“You can fill up a hydrogen bus in roughly 10 minutes. In a battery electric bus you can use almost half of the battery on the heater alone, while there’s no distance compromise with the fuel cell. These will get 250 miles while you are looking at a 100-mile range with the battery electric bus.”

While examples such as this show why it is clear hydrogen is suited to larger vehicles, it may be less obvious why the fuel is relevant for passenger cars.

“I think hydrogen will be really important in heavier vehicles and non-automotive applications, such as shipping,” says Tom Callow, director of communication and strategy at BP Chargemaster.

“What I can’t quite get my head around is how a hydrogen passenger car will end up being a more compelling proposition that a pure EV, other than as a real niche – a 3% type niche – product. The EV charging infrastructure, battery capacity and everything else is accelerating at such a pace I can’t see it stacking up economically.”

However, the argument is not that FCEV should replace BEV in all applications, but should complement it, dependent on user requirements.

“For smaller vehicles and lower distances travelled, BEVs are perfect,” says Paul Marchment, senior business manager at leasing company Arval, which has carried out a series of hydrogen roadshows to raise awareness of the technology.

“You plug them in, drive to the office, and as most people only do 20 miles a day, electric cars will suit them. For the occasional longer trip, they might consider a plug-in hybrid.

“When you get to the drive cycles that demand a lot of distance and a lot of time, that’s where hydrogen works because it’s so easy to fill up.

“I can fill my Toyota Mirai from empty in about four minutes, that 4.5kg of hydrogen gets me about 300 miles and the only emission is water, so what’s not to like?”

Obvious answers are the current lack of availability and cost of FCEVs and the limited refuelling infrastructure.

However, both scenarios will change in the future, according to Jon Hunt, manager alternative fuel at Toyota.

“By 2025, you will start to see all the main carmakers having a fuel cell in the market,” he says. “Between 2025 and 2030 is when you will start to see an acceleration. Again, it won’t be commonplace everywhere but in certain areas: California has mandates, but also the desire, to change and so do markets like the UK.

“Post 2030 is when you will start to see that real push, and that will be driven not only by the adoption of new cars, but simply because you won’t be able to achieve the average emission requirements with any other solution.”

Toyota and Hyundai lead the way

Toyota and Hyundai are leading the development of FCEVs, while Honda also has experience of the technology with its FCX Clarity.

BMW is expected to launch an FCEV in 2022, while Hyundai last year entered a cross-licensing agreement with Audi for fuel cell technology, with the German manufacturer announcing it would intensify its development of hydrogen fuel cell technology by re-establishing its h-tron programme.

It says a limited-volume Audi FCEV could be offered as part of a lease programme by 2021, with volume production of models during the second half of the next decade.

Audi cited concerns over the sourcing of natural resources for battery production and doubts over electric cars being able to deliver on ever-more-demanding customer expectations to explain why it was investing in hydrogen technology.

Renault will launch FCEV versions of its Kangoo ZE and Master ZE battery electric vans next year, providing up to three times the range of the BEV models while taking a fraction of the time to refuel.

The technology will see the Master ZE’s range increase from 75 miles to 218 miles in the Master ZE Hydrogen, with the Kangoo ZE Hydrogen offering 230 miles, a rise of 87 miles.

“These vehicles provide professionals with all the range they require for their long-distance journeys as well as record charging times,” says Denis Le Vot, Alliance SVP of the Renault-Nissan LCV Business Unit.

Vehicle costs will also fall. The two FCEVs available in the UK retail at almost £70,000, but it will not be long until the price of hydrogen cars falls more in line with conventional vehicles.

“It’s difficult to forecast because it is dependent on volumes, but we pretty clearly indicated that around the mid-2020s, you will have price parity with conventional cars,” says Hunt.

This is because the cost of the components is no more than the material cost for a conventional car. FCEVs don’t require the same emissions control systems, the amount of platinum in the fuel stack is not much different than in a diesel catalyst, and there are no oils.

“Overall, at scale you could achieve a lower price point – but it’s that scale you need,” Hunt says.

“We do get a bit too hung up, generally, on the purchase price. In the fleet market, the cost of ownership is more important and the vehicle’s residual value (RV) is the biggest part of that.

“The interesting thing with fuel cells is that your operational costs can be low because in the fuel cell system there is just one maintenance part which is a de-ionising filter like you have at home on your hot water system, which needs replacing every 30,000 miles.

“So, when you look at the maintenance and you consider your RV, the fuel cell system will hold an intrinsic value because the components in the fuel stack itself are designed not to wear out and will still do the same job as it did when made.

“You can put it in another powertrain, you can use it for stationary power, you can recycle 100% of it, so you’ve got a value in the component which is maintained and that means your RV has a bottom because it always has a market.

“You will dispose of your internal combustion engine car when it becomes too expensive to maintain the engine, transmission or other components; you will do the same with a BEV when the battery degrades to a point when it is not usable.

“This simply won’t happen with an FCEV.”

While future launches will increase the number of FCEVs in the UK, the number is currently tiny – combined, 150 Mirai, Nexo and Hyundai ix35 hydrogen-powered cars, and a handful of buses.

Chicken and egg situation

This creates a chicken and egg situation when it comes to providing and expanding the refuelling infrastructure, says Smith. At the moment there are just 17 publically-accessible refuelling stations.

Phil Killingley, deputy head of the Office for Low Emission Vehicles, adds: “You can take different approaches to the roll-out of hydrogen refuelling stations. You can scatter the country and hope the vehicles come along, or, given that the vehicle supply is relatively limited, you can seek to achieve high utilisation of stations with captive fleets and it is the latter approach we have gone for in the UK.”

Hydrogen has the advantage that stations can use renewable energy on site to create hydrogen through electrolysis, meaning that as well as the process being eco-friendly, they do not have to be connected to a wider refuelling network or grid.

However, the infrastructure will never be able to match that of BEVs, with home and work-based charging accounting for a large proportion of its refill requirements.

Alternatively, hydrogen can be created through industrial processes and transported to the stations.

Five of ITM’s stations are in the London area and are used by fleets including private hire firm Green Tomato Cars (see case study, page 30), which is operating around 50 Mirai models, and the Metropolitan Police which has 21.

“Our stations are based on who has got a fleet that wants them,” says Smith. “For example, there is a gap in the network between Sheffield and Aberdeen and we could easily put a station in there, but if there is not a fleet to use it, then it wouldn’t be a project we would go ahead with.”

Smith says a great example of how it can roll-out hydrogen refuelling stations is its Birmingham bus project, which will open in Q1 next year to provide fuel for 20 hydrogen buses.

“The reason our project in Birmingham is so key is that it concentrates on that fleet of buses, and we can then say let’s put a public refuelling station on it as well,” he adds.

“That’s how I think the refuelling infrastructure will initially be expanded.”

How safe are fuel cell vehicles?

“A lot of people say ‘hydrogen, it’s going to explode’ and hydrogen does have a high energy density, but if you manage it safely then it does a good job and is super safe,” says Sylvie Childs, senior product manager at Hyundai.

Its Nexo was the first FCEV crash-tested by Euro NCAP and achieved the maximum five-star safety rating.

“Its rating should dispel concerns around how hydrogen fuel cell powered vehicles perform in a crash,” says Matthew Avery, director of research at Thatcham Research.

“With the Nexo, Hyundai has successfully demonstrated that alternative fuelled vehicles need not

pose a risk to car safety.”

Toyota has taken a similarly thorough approach to safety for Mirai: each of the materials chosen for its hydrogen tank has been selected to contain the fuel safely. Its carbon fibre-wrapped polymer-lined tanks absorb five times the crash energy of steel.

In a collision, the hydrogen system shuts off to prevent the gas from travelling to potentially damaged systems outside of the tank.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.