The ‘big freeze’ in fuel duty lasting more than 10 years has cost the Government about £80 billion in lost tax revenue.

And the rising take-up in electric vehicles is expected to cost the state £13bn a year by 2030.

Does society realise the consequences of this? And are we ready for them? Or should we address the inequity in tax take to improve society for the most amount of people?

These were questions posed by Anna Rothnie (pictured), principal transport planner for Mott McDonald and co-author of a report from the Greener Transport Council, called ‘Paying for driving: is doing nothing an option?’, at the December Fleet200 Strategy Network meeting.

She recalled the protests in 2000 in response to rises in fuel duty, which led to a reduction in the rate petrol and diesel prices increased, followed by a protest against the principal of road user pricing – including a 1.7 million signature petition – that meant the topic was ‘binned’ and became “hush-hush” ever since.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 saw a further 5p duty cut, then most recently the Labour Budget confirmed there would be no change to fuel duty rates.

“Fuel duty is the ninth largest source of income for the Government – about 2.3% of our tax. Or more than half as much as council tax,” Rothnie said.

The ‘big freeze’ in fuel duty lasting more than 10 years has cost the Government about £80 billion in lost tax revenue.

And the rising take-up in electric vehicles is expected to cost the state £13bn a year by 2030.

Does society realise the consequences of this? And are we ready for them? Or should we address the inequity in tax take to improve society for the most amount of people?

These were questions posed by Anna Rothnie (pictured), principal transport planner for Mott McDonald and co-author of a report from the Greener Transport Council, called ‘Paying for driving: is doing nothing an option?’, at the December Fleet200 Strategy Network meeting.

She recalled the protests in 2000 in response to rises in fuel duty, which led to a reduction in the rate petrol and diesel prices increased, followed by a protest against the principal of road user pricing – including a 1.7 million signature petition – that meant the topic was ‘binned’ and became “hush-hush” ever since.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 saw a further 5p duty cut, then most recently the Labour Budget confirmed there would be no change to fuel duty rates.

“Fuel duty is the ninth largest source of income for the Government – about 2.3% of our tax. Or more than half as much as council tax,” Rothnie said.

“We complain about potholes and the state of the NHS as well as other things, while accepting that the cost of motoring is decreasing compared to other areas of life.

“So, we have to ask ourselves what outcomes do we want for our society, what quality of life do we expect for our friends, family children and grandchilden? Do you want society to be fair, to be cleaner?

“Because when you look at the unintended consequences of a loss of ability to fund improvements to society, the results should make us stop and think.”

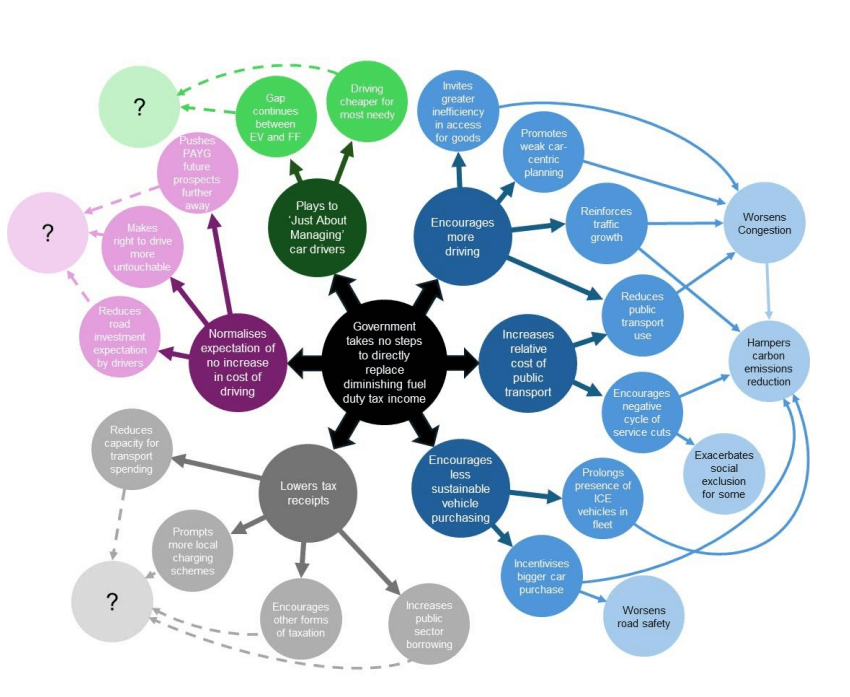

Using a concept called the futures wheel (see below), created with the input from 22 transport sector experts for the ‘Paying for driving’ report, Rothnie revealed the immediate impacts of a continuation of benign fuel duty policy on society.

The ‘first order’ impacts include:

- Encourages more driving

- Increases the relative cost of public transport (particularly after the increases in the cap on bus ticket prices in the 2024 Budget)

- Encourages less sustainable vehicle purchasing

- Normalises the expectation of no increases in the cost of driving.

Then beyond the ‘first order’ impacts Rothnie warned of further increases in traffic volumes, in turn the negative impacts on road safety and pollution, prolongs the presence of petrol and diesel vehicles, and with lower tax receipts, there is a potential reduction in transport spending and increases public sector borrowing.

The report says: “In life, if something looks too good to be true, then it probably is.

“The equity implications are much wider than ‘making driving cheaper’. How much people (and businesses) pay for driving is about to become very different and, we would argue, one of the most unfairly distributed tax burdens in the economy:

- For those who continue to drive: Those who can shift to electric will pay around one sixth of the cost per mile as a driver of a fossil fuel vehicle if they have off-street charging at home. As EV purchase prices fall this differential will essentially fall first to the wealthy who buy newer EVs, and will take many years to flow through to everyone.

- For those who cannot drive, their public transport services will be eroded further.

Rothnie highlighted initiatives elsewhere in the world that could address the issues raised by rebalancing the tax take from motoring and the need to fund societal improvements:

- In New Zealand a pay-per-mile scheme has been introduced exclusively for EV car drivers and diesel commercial vehicles over 3.5 tonnes

- A European pay-per-mile scheme for commercial vehicles over 3.5 tonnes in multiple countries

- A voluntary contributory programme for drivers in several US states, predominantly for EV drivers.

The report concludes: “With a new Labour Government holding an overwhelming majority in the House of Commons, we suggest that there has never been an easier time to make one of the most difficult decisions in transport policy.”

Further source on road-user-charging schemes outside the UK: ‘Charging for road use: what is the future of mobility pricing?’

Login to continue reading.

This article is premium content. To view, please register for free or sign in to read it.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.