Shifting passengers away from public transport and into self-driving cars may have the effect of increasing traffic volumes, warn experts. By Jonathan Manning

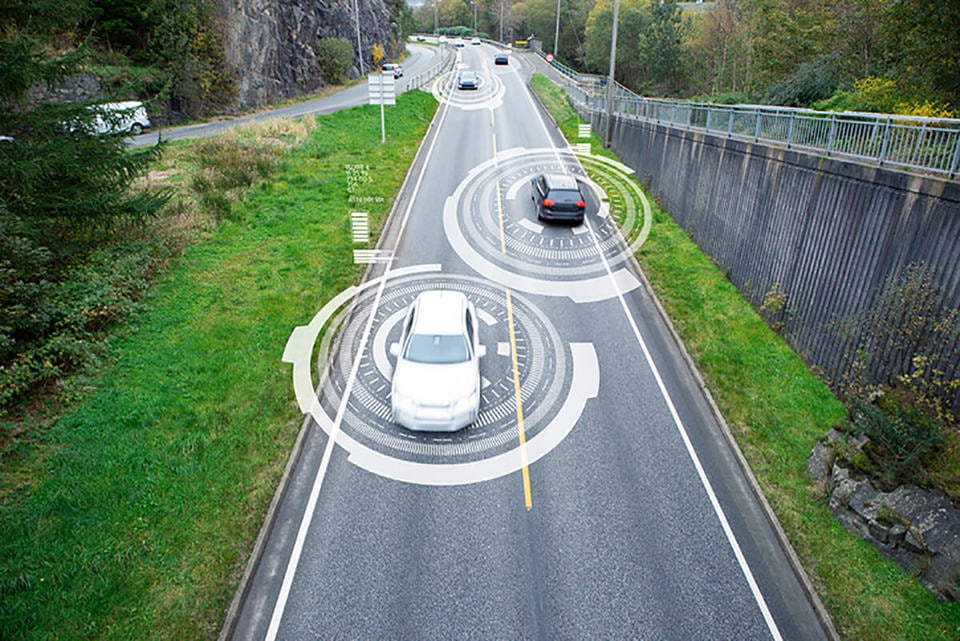

Nirvana may look like free-flowing city streets with autonomous vehicles driving, accident-free, just millimetres from each other, but a number of experts have warned that this vision of the future may be more science fiction than science fact.

They caution that driverless vehicles will not mean the end of congestion and that major investment will still be required in public transport infrastructure.

In theory, autonomous vehicles should facilitate the optimal use of the UK’s road network. By smoothing the way vehicles drive and removing the risk of a loss of attention by the driver, autonomous cars will potentially be able to drive more closely together, thereby increasing the capacity of the road network.

"If it takes 50 people out of a well stacked double-decker bus and smears them out into pods, that is not going to be the right way for the network.” Michael Hurwitz, (below) director of transport innovation at TfL

In addition, connectivity with traffic planning systems should ensure smoother journeys, with speeds controlled between traffic lights and junctions to minimise queuing.

But there’s no escaping the fact that fleets of empty, driverless cars circulating in cities will create congestion as stifling as today’s urban centres suffer.

Braced for in excess of a million more residents by 2030, Transport for London (TfL) calculates the capital will see an additional six million trips every day by 2040, which will intensify pressure on the city’s limited road space.

TfL’s overarching ambition is therefore, “to encourage the use of more efficient, low-emission vehicles, and overall less car and van use.”

This will involve a mode shift towards sustainable means of travel, such as walking, cycling, and public transport from 65% today to 80% by 2041 (the date is planned around the census), says Michael Hurwitz, director of transport innovation at TfL.

“We have to, in a city of London’s density and limited geography, invest in mass transit,” he told delegates at Shell’s Powering Progress Together conference.

Single-occupancy car journeys are bad for congestion whether the vehicles are autonomous or not, added Hurwitz.

“Can you provide an alternative for people commuting on their own in vehicles carting around three empty seats?” he asked.

“If it takes 50 people out of a well stacked double-decker bus and smears them out into pods, that is not going to be the right way for the network.”

Autonomy is the only economically viable way to replace cars with an alternative form of shared transport, according to Stan Boland, chief executive officer of Five AI, which specialises in the delivery of autonomous shared transport services.

But this “has to be done in collaboration with public transport. We cannot cannibalise public transport systems, we have to support them,” he says.

The economics come into play due to the cost of the driver.

Take, for example, the cost of Hurwitz’s 50-seater double-decker. Were it to be replaced by a fleet of five 10-seater minibuses, travellers could look forward to five times as many services, shorter waiting times and a more attractive offering.

Today, this solution would also include the cost of five drivers instead of one and, therefore, be five times as expensive.

Five shared, autonomous vehicles without drivers, however, would cut these additional costs considerably and improve the service.

Moreover, large vehicles are typically inefficient outside peak times – a 50-seater double decker with just a handful of people on board is financially and environmentally inefficient, said Brad Templeton (below) chairman emeritus and futurist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

He forecasts that “smaller vehicles are likely more optimal once we eliminate the need for drivers and move to a highly communicating world.

"There are strong arguments that while shared travel is beneficial, we actually have too much of it in most transit systems and not enough in private cars.

"The ‘shared’ future is one of van-sized group vehicles with a mixed fleet of more personal cars with one to four seats.”

One of the conclusions of last year’s exhaustive study into connected and autonomous vehicles (CAVs) by the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee was that “the theoretical potential of CAV to reduce traffic congestion varies dependent on the level of vehicle autonomy and the penetration rate”.

It adds: “While we cannot say with any certainty what the impact on congestion will be, it is possible to imagine a situation of total gridlock as CAVs crawl around city centres. It is important that the right policy decisions relating to CAVs are made in order to reduce the likelihood of this occurring.”

In response, the Department for Transport agreed that: “The effect of CAVs on congestion is uncertain.

"Congestion is a function of the capacity and performance of the road network, and the level of demand in a certain place at a certain time.

"As for the impact of CAV technologies on the level of demand, the potential impacts are very complex and further research is needed in order to understand the possible impacts on congestion and what policies may be required to manage these effects.”

Ride hailing adds to congestion

New York City Council has voted to issue no new for-hire vehicle licences for 12 months, citing the impact of fast-growing firms such as Uber and Lyft on congestion.

Council member Stephen Levin said: “In just a few years, the number of for-hire vehicles in our city has increased dramatically, snarling traffic. An average of 2,000 additional vehicles hit the streets every month while drivers already spend nearly half their time with empty seats.”

The bill will give the city’s Taxi and Limousine Commission time to study the issue, which is also tightly bound up in the wages earned by ride-hailing drivers.

Bill de Blasio, mayor of New York, said: “We are… halting the flood of new cars grinding our streets to a halt.”

A statement from Uber said: “Demand for rides has grown every year since Uber entered New York City, and with a public transit system in crisis, this trend is likely to continue.

"If there are not enough driver-partners on the road to meet growing demand, reliability for riders could decline, and they would likely choose other transportation options instead of requesting Uber trips.”

In a new study, published at the end of July, Bruce Schaller, principal of Schaller Consulting and a former deputy commissioner for traffic and planning at the New York City Department of Transportation, found that Transportation Network Companies (TNCs) such as Uber and Lyft, have added billions of miles of driving in the US’s biggest cities at the same time as the growth in car ownership outstripped the rise in population.

He said TNCs compete mainly with public transportation, walking and cycling, rather than traditional taxis or private cars, thereby adding to road travel and increasing congestion.

“About 60% of TNC users in large, dense cities would have taken public transportation, walked, biked or not made the trip if TNCs had not been available for the trip,” said Schaller.

He added that for every private mile removed from city streets, TNC services add 2.8 miles of car travel (the mileage between trips as the ride hail vehicles travel from one customer to another

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.