Vehicles driven by the internal combustion engine (ICE) look like they are losing out to alternative fuel power trains. Simon Harris reports

Looking at a typical company car fleet 20 years ago, it would have been dominated by traditional car sectors.

This would have changed little compared with the previous 20 when Fleet News was launched in 1978.

By 1998, large MPVs were not uncommon, driven by the success of early pioneers such as the Renault Espace and in the 1990s, the Chrysler Voyager.

But by the late 1990s, Renault had created a new multi-purpose vehicle (MPV) niche, with the Megane Scenic (later, just Scenic). Vauxhall had turned the concept into a seven-seater with the Zafira. Others were to follow.

The mid-1990s witnessed the introduction of smaller sport utility vehicles (SUVs) with car-like driving characteristics, such as the Toyota Rav4, Honda CR-V and Land Rover Freelander.

Soon the premium brands would introduce larger crossovers, such as the Mercedes-Benz M-Class (now GLE), and Lexus RX.

Meanwhile, fleets still bought executive cars from mainstream brands, such as the Ford Scorpio, Vauxhall Omega, Renault Safrane, Citroën XM and Peugeot 605.

Now, 20 years on, the picture is quite different, and continuing to evolve as a result of several factors.

The rise of premium brands and proliferation of new model lines has made traditional mainstream choices less attractive for fleet customers and company car drivers, while some manufacturers have decided certain models that thrived as a result of fleet business are no longer viable.

At the same time crossovers have penetrated fleet choice lists, despite their higher purchase price than similar-sized hatchbacks or estate cars, and the choices have broadened to encompass all sizes.

The tax regime since 2002 has favoured lower CO2 emissions and, while thresholds have tightened over the years, internal combustion engine (ICE) technology has more or less kept pace.

But the current climate appears to punish the latest generation of diesel cars – still the essential fuel choice for many fleet roles – more harshly than it should, with a four-percentage point premium over a petrol car with the same level of CO2 emissions.

Other negative stories around diesel emissions have prompted reviews among fleet operators, while a growing choice of zero-emission, plug-in hybrid and self-charging hybrid cars has encouraged user-choosers to demand electrified power trains as they seek to minimise tax liability.

A study by Sewells Research and Insight shows that while fleets might have more rigid parameters than retail consumers when choosing cars, there is also evidence of the appeal of some vehicles at the expense of those traditionally thought of as ‘typical’ company cars.

Traditional choices in decline

Looking at the range of cars available from any mainstream manufacturer illustrates how consumer tastes have evolved over the years.

Just 10 years ago, virtually every mainstream car manufacturer offered an upper-medium saloon or hatchback, and it’s a sector that still has a greater share of fleet sales than private.

Excluding premium brands, Chevrolet, Citroën, Fiat, Ford, Honda, Hyundai, Kia, Mazda, Peugeot, Renault, Škoda, Subaru, Toyota, Vauxhall and Volkswagen all had cars in this sector – a list of 15 brands.

A year earlier, Nissan dropped the Primera from its range in favour of the Qashqai.

That list has halved at this point in 2018 (although Renault offers the Talisman saloon and estate in left-hand drive European markets), as car manufacturers have responded to falling demand for this type of car, and the increased appeal of alternatives.

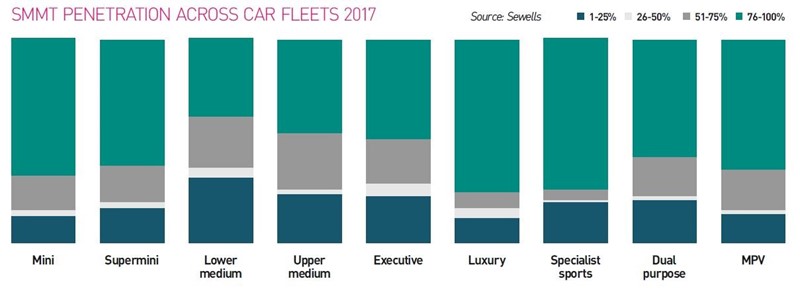

According to Sewells, the number of organisations in the UK with upper-medium cars on their books increased from 2016 to 2017, although there was a change in the level of penetration.

The number of fleets where upper-medium car or D-sector penetration was at least three-quarters had declined from 31% to 24%. But the number of low-penetration fleets (with D-sector models making up to a quarter of company cars) has increased from 39% to 46% from 2016-2017.

Overall, the fleet penetration of this sector fell from 45% to 44% year-on-year, which, although it appears to follow the trend, is perhaps a more gradual decline than expected.

But there are two possible rationales behind this: one is the continued importance of the sector to fleets (corporate sales still account for as much as 80% of this sector’s sales for some brands) and the fact that the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) definition of upper-medium also includes premium-badge models.

Therefore, the increase in sales to fleets of models such as the Mercedes-Benz C-Class could partially or fully offset a decline in sales of the Ford Mondeo.

Of all the SMMT-defined sectors included in the Sewells research, the upper-medium sector remains one of the most popular.

Mainstream car manufacturers that have participated in this sector seem prepared to continue.

Peugeot is launching a new 508 saloon model, with an estate version due for unveiling at October’s Paris motor show.

Although the Citroën C5 disappeared from price lists a few years ago, the company maintains the nameplate is merely resting, with a new model ready to take its place in the range alongside the new C5 Aircross SUV.

And while Toyota stopped Avensis production earlier this year, it plans to introduce a European version of the Camry, which was always much more successful in North America, Australia and New Zealand than in Europe in previous generations.

Larger than the Avensis, the Camry went off sale in the UK more than 10 years ago.

However, there could come a time that mainstream car manufacturers will give up on the upper-medium sector.

Scott Gairns, managing director of Sophus3 (below), a company that works with vehicle manufacturers by monitoring their digital marketing and communication activities to help them gain more value, believes declining sectors could well become unsustainable.

Many private consumers and fleets have already deserted mainstream upper-medium sector cars in favour of SUVs, while smaller hatchbacks have also come under pressure.

But the D-sector is possibly more vulnerable in terms of its declining volume in the years ahead, despite relatively high demand from fleet operators.

Gairns says: “As there is continually less interest in this sector we will probably see more car manufacturers leave, given the economies of scale that were there previously will disappear.”

For now, however, fleets surveyed by Sewells believe there will be some growth in their upper-medium car parcs during 2018, with an average of 0.6% cited, the strongest predicted sector growth in the research.

According to Sewells, lower-medium cars have a stronger presence on fleets than upper-medium models, and the average penetration is higher at 50% in 2017 – increasing from 48% a year earlier.

That said, only the organisations where penetration is up to a quarter have increased year-on-year, with higher penetration fleets undergoing a slight decline.

Like the upper-medium sector, the numbers will be boosted by premium-badge cars of the same size, and the proportion of premium models on fleets is likely to increase.

Audi can claim to have invented the premium family hatchback in 1996 with the A3. The model still sells strongly and has saloon and convertible versions alongside the hatchback.

Mercedes-Benz’s latest A-Class will be offered with a saloon version for the first time, and the company spreads the platform’s cost more evenly by also offering the CLA four-door coupé and Shooting Brake estate.

With increased interest in premium-badge cars, as well as more choice, these, along with other premium-badge cars, are making the sector longer lived in the face of attractive crossover alternatives.

The research by Sewells suggests fleets will see 0.3% growth in the lower-medium sector on their fleets this year.

The executive car sector is also forecast to grow on fleet in 2018 after increasing its penetration from 39% to 43%, according to the Sewells study, and appear on 12,000 more fleets in 2017 than in 2016.

The sector is almost entirely made up of premium-badge cars during the timeframe of the research, and these have diversified in recent years beyond the traditional saloon and estates.

Alongside the Mercedes-Benz E-Class saloon and estate is the CLS four-door coupé and Shooting Brake estate, while Audi has the A7 Sportback alongside the A5 saloon and Avant.

BMW, until last summer, offered a four-door 6 Series Gran Coupé as an upmarket alternative to the 5 Series saloon and Touring, as well as the 5 Series Gran Turismo (since late 2017 its replacement has been a member of the latest 6 Series family).

Volvo’s S90 and V90 models have been taken more seriously than their predecessors in this sector, and to many are seen as genuine alternatives to the German premium brands while offering something with its own identity.

The increased appeal of these cars, as well as alternatives such as Lexus, with hybrid power that doesn’t carry some of the tax penalties and the negative connotations of diesel, could be helping boost this sector in the eyes of fleet operators and company car choosers.

Specialist sports cars, in SMMT-speak, coupés and convertibles, increased their presence on fleets between 2016 and 2017, with 15,000 more fleets including them on their choice lists compared with a year earlier, at 61,000.

These cars are as far removed from job-need vehicles as it’s possible to be. They are never chosen for practical reasons, and are almost always a perk.

They became less common choices on fleets during the last recession sparked by the financial crisis of 2008, as many organisations were exploring ways to reduce spending.

As job losses meant an inevitable reduction in company car fleet size, offering a specific level of car to aid staff retention seemed redundant.

They are often difficult for fleets to redeploy when staff using them leave the company because the new recipient might need something more practical as their company car.

For now, these vehicles are in some kind of ascendancy with fleets, albeit in low volume. They are most often found among smaller organisations where penetration of is up to a quarter of the fleet size.

It could mean the combination of higher residual values (through these being more desirable and exclusive vehicles than typical fleet choices) and new power train technology bringing down fuel costs and BIK taxes to an acceptable level make them suitable choices for some employees, and that staff retention is becoming a greater factor for certain businesses.

MPVs are a relatively new presence in the history of motorised vehicles, but their peak might well have been reached some time ago.

According to Sewells, the MPV sector on fleets fell by three percentage points between 2016 and 2017, with 4,000 fewer fleets using the vehicles.

It’s a long time since large MPVs had a major presence in the fleet sector and all but a few mainstream manufacturers have abandoned this sector. But their compact counterparts are also in decline.

Vauxhall no longer offers the Meriva compact MPV, and, in 2017, Ford discontinued the Fiesta-based B-Max after one lifecycle.

Some manufacturers have switched emphasis to SUVs, with Peugeot transforming its 2008 (essentially a raised 208 estate), 3008 and 5008 into an SUV family.

Sister brand Citroën has dropped the Picasso name adopted for some of its MPVs, and the C3 Picasso MPV was replaced by the C3 Aircross SUV.

The C5 Aircross will arrive at the end of the year, while its large van-based MPV, the SpaceTourer, has given its name to the former C4 Picasso.

Citroën and Peugeot have a van-derived MPV in their ranges with the latest Berlingo Multispace and Rifter, while Ford, Vauxhall and Volkswagen have van-based vehicles alongside their car-based MPVs, the ones with origins in LCVs seen as spacious, budget alternatives to the more sophisticated car versions.

But as the sector declines, we could be reaching a tipping point for the future of the medium-sized MPV.

When asked at the unveiling of the C5 Aircross if there was room in the Citroën range for two medium MPVs (Berlingo Multispace and C4 SpaceTourer) in the future, Citroën CEO Linda Jackson told Fleet News guardedly: “That’s a very interesting question, and one that we are currently considering.”

The Berlingo Multispace has just launched as a third-generation model, while the C4 SpaceTourer is mid-lifecycle. Jackson wouldn’t be drawn on whether there would be a direct replacement for the C4 SpaceTourer, but trends suggest it could be difficult to justify and customers might have sought SUV alternatives by then.

Gairns has sat in on future model planning meetings with car manufacturer clients.

“I haven’t been in any meetings recently where MPVs were talked about,” he says.

Small cars take a huge proportion of European car sales, but UK fleets have seen their penetration decline between 2016 and 2017, with further falls in penetration expected.

Both B-sector (cars such as the Ford Fiesta and Vauxhall Corsa) along with the A-sector (cars such as the Vauxhall Viva and Fiat 500) appear to be falling out of favour.

Average fleet penetration of B-sector models has fallen from 35% to 33% from 2016 to 2017 and Sewells research predicts a further 0.8% fall this year. A-sector cars have fallen from 32% to 30%.

Often, a B-sector vehicle would be an entry-level company car for those that need them. But they would also have a strong presence on daily rental fleets, as well as courtesy cars and pool cars.

It’s possible that with the greater provision and availability of other transport choices, fleets might have less use for small cars on long lifecycles, and perhaps prefer to use daily rental, car club or ride hailing schemes to fill the gap.

At the same time, as car manufacturers have realised the SUV formula appears to work on medium and large cars, they have sought to introduced smaller versions that in some cases might be a more attractive alternative to a conventional small hatchback on company car fleets.

The rise of SUVs on fleets

According to the research by Sewells, SUV (dual-purpose, according to the SMMT) presence on fleets increased only modestly between 2016 and 2017.

This perhaps hides the level of growth we’ve witnessed during the past 10 years or so, thanks to the evolution of SUVs and crossovers.

‘Crossover’ is essentially a marketing term used by the industry for selling the idea that a car has combined the merits of two distinct genres, initially setting apart a 4x4 based on a monocoque structure, more like a car platform, rather than the body-on-chassis construction of traditional 4x4s.

Early examples, such as the Toyota Rav4, Land Rover Freelander and Honda CR-V, introduced in the mid-1990s, were popular, but the change in benefit-in-kind (BIK) tax from a business mileage-based system to car CO2 emissions in 2002 began to hit drivers in the pocket.

They became less appealing to choose as company cars, but Nissan introduced the Qashqai in 2007, which was widely seen as a pioneer.

It took up no more space on the road than the Nissan Almera hatchback and had similar fuel efficiency.

It offered the raised driving position and ground clearance of an SUV, but most versions were offered as front-wheel drive cars.

Other manufacturers were readying their own versions, including the Ford Kuga and Volkswagen Tiguan, while the latest versions of formerly innovative models like the Rav4 and Freelander, began to look rather dated.

Other manufacturers were readying their own versions, including the Ford Kuga and Volkswagen Tiguan, while the latest versions of formerly innovative models like the Rav4 and Freelander, began to look rather dated.

And while the SMMT classes all SUVs under ‘dual purpose’, the category covers four or five sub-classes within it, as many of the vehicles are derived from the same platform as a car that fits into one of the other groups.

Nissan downsized the formula that delivered the Qashqai in 2010 to introduce the Juke, while many car manufacturers were still coming up with rivals for the Qashqai.

According to vehicle market analyst Jato Dynamics, the SUV sector accounted for most of the growth in the car market in 2017.

In the UK, around 812,000 of the cars registered in 2017 were SUVs.

Felipe Munoz, global car market analyst at Jato Dynamics, believes further growth in SUVs is to be expected.

“Previously, major carmakers like Volkswagen Group and Hyundai-Kia took a backseat when it came to SUVs,’ he said.

“The Volkswagen brand finally got involved in the segment though after launching the Atlas/Teramont in the US and China, the T-Roc in Europe and a longer version of the Tiguan for global markets.

“Then Škoda introduced the Kodiaq and Karoq, and Seat brought the Ateca and Arona to the market.

“More are scheduled to come, with the VW T-Cross, Seat Tarraco and a smaller Škoda all set to be released.

Meanwhile, Hyundai-Kia wants to boost sales with the launch of its first global small SUVs: the Hyundai Kona and Kia Stonic (launched in 2017 and 2018 respectively).”

Growth in the SUV sector in the UK last year was lower than other key European markets, which was perhaps a sign of a more mature market for the vehicles here, as well as a lacklustre year for new car sales.

In the Sewells research, average fleet penetration for SUVs increased from 37% to 38% between 2016 and 2017, with a 0.5% increase expected in 2018.

Debbie Floyde, Bauer Media fleet and risk manager, says she now has an SUV and a hybrid option on each of the business’s company car scheme bands.

“Although choice is restricted somewhat, SUVs are the favourite. Traditional hatchbacks such as the Volkswagen Golf and BMW 1 Series are popular, but so far the Kia Sportage and the Ford Kuga with its CO2 emissions are more competitive.

I anticipate a lot of interest in the Seat Ateca and Škoda Karoq too.”

The influence of BIK tax

If BIK tax initially deterred the appetite for SUVs, and forced manufacturers to come up with more fuel-efficient alternatives with broader appeal, recent changes to the tax could help define future trends.

In 2018, the BIK tax supplement on diesel cars grew to four percentage points over petrol cars producing the same level of CO2 emissions.

Along with CO2 readings being revised for the new official WLTP testing regime, company car tax could be in for its steepest rises for many years.

Fleets are already reporting drivers seeking to reduce their tax liability.

Floyde said: “The majority of employees are cost-conscious these days and are looking for minimal BIK as well as low fuel consumption.”

A wider choice of petrol-electric hybrid cars has given drivers and employers more of a choice if diesel is no longer a cost-effective option, or they are fearful of the effects of future legislation on residual values.

Hybrid pioneer Toyota ended the choice of diesel engines in its car line-up in 2018, with the exception of the Land Cruiser, while the new Auris, due in 2019, will have a standard and a higher performance hybrid choice.

Kia offers a petrol-electric hybrid in its Niro crossover, as well as a plug-in hybrid version, and a plug-in hybrid alternative to diesel in the Optima.

A fully electric Niro is also available, reflecting the power train choices of sister brand Hyundai in its Ioniq hatchback.

Plug-in hybrids offer significantly lower CO2 emissions than standard petrol or diesel cars and, despite a price premium, often greatly reduce BIK tax liability.

One of the most prolific plug-in hybrids on UK roads, the Mitsubishi Outlander, was the first that managed to combine the appeal of emissions-free commuting and the styling of an SUV with transaction prices comparable to the diesel version.

The SUV seems to be the most advantageous vehicle for accommodating additional hybrid components with the least compromise to practicality, and this would appear to help demand for SUVs to hold firm if diesel continues its current decline.

According to figures from the SMMT, alternative fuel vehicles, which includes all types of hybrids and electric vehicles, have witnessed a 23.8% increase in registrations for the first seven months of 2018, reaching more than 80,000 units.

But plug-in hybrid options are also available in hatchbacks, saloons and estates, such as the Audi A3 Sportback, Volkswagen Golf and Passat, BMW 2 Series Active Tourer, 3 Series and 5 Series, and Mercedes-Benz C-Class and E-Class, as well as SUVs.

Paul Tate, fleet manager at Siemens, says around 50% of the orders for its 700-plus car fleet are now plug-in hybrid.

He explains: “Tax is now the main driver behind vehicle choice, with drivers seeking lower BIK alternatives, and this is across all sectors.”

It’s likely, therefore, that future fleet choices will create stronger growth in the sectors that offer the greatest number of hybrid and plug-in variants.

An electrified future?

Car manufacturers should be selling even more alternative fuel vehicles than are currently being registered, according to Gairns.

Sophus3 monitors consumer journeys while they are in the car-buying process, including use of fleet-specific sections of car manufacturer websites.

Gairns says that for the latest electric vehicles, car manufacturers are failing to lead consumers through the choosing process in the way they expect, resulting in high levels of potential buyers abandoning the process part of the way through.

“One of the main reasons people drop out of the journey is they can’t find the information they need,” he says.

“There is a level of complexity around using EVs that you don’t get with an ICE vehicle, and it’s not easy for customers to gather the necessary knowledge from online searches.

“Consumers researching online are used to a buying process as convenient as Amazon, that’s not what car manufacturers are offering.”

But he adds that he also expects the growth in SUVs to continue, with greater availability of hybrids and electric versions.

It seems the traditional car sectors that served fleet for several decades with little change are now support acts in specific fleet roles to the lead of more appealing SUVs.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.