Autonomous-driving small vans, low-speed robots and high-flying drones are just some of the methods being trialled as home delivery sector seeks answers to one of its biggest problems. By John Lewis

Had you visited the Royal Arsenal Riverside housing development in Greenwich, south-east London last June, you might have witnessed – perhaps without realising it – what could turn into a home delivery revolution.

An electric van was bringing Ocado groceries to residents. But it was a van with a difference. Although there were two people in the cab – one from the retailer, one from the vehicle manufacturer – it was driving itself and busy making the UK’s first autonomous deliveries.

Called CargoPod, it is built by Oxbotica and controlled by the Oxford-based company’s Caesium cloud-based fleet management software in tandem with its Selenium autonomous control system. It can carry a modest 128kg (a bit less than the weight of a giant panda).

Its body has eight compartments. When it arrives at a residence, the compartment containing the customer’s groceries illuminates. The customer presses a button which unlocks the compartment and its contents can be collected.

Selenium employs data from lasers and cameras placed around CargoPod which allow the vehicle to know where it is, what’s around it and where to go next.

The lasers play a key role because they detect obstacles in its path and the little van, which has an 18-mile range, will stop immediately if somebody steps in front of it.

The trial formed part of the government-backed GATEway (Greenwich Automated Transport Environment) Project, an £8 million initiative led by Transport Research Laboratory in collaboration with Oxbotica, Digital Greenwich, Telefonica and others. It took place in a self-contained area on private roads – CargoPod has a top speed of 25mph but was restricted to 5mph for the purposes of this exercise – and Ocado feels it was a success. More than 100 deliveries were made during the 10-day experiment.

CargoPod, however, is just one of a variety of approaches to solving the biggest conundrum fleets delivering consumer goods face: how best to tackle last-mile deliveries.

Next time you walk down the street in a major city you might encounter another way of addressing the problem – a small, six-wheeled, self-driving robot. It can navigate its way around obstacles and people as it trundles along pavements at a stately 4mph.

Developed by Starship Technologies, some 150 of these robots have been built so far and they are in service in cities worldwide, including London. Hermes has trialled them in another part of south-east London – Southwark.

“We’ve got 25 in the UK, with some operating in Milton Keynes,” says chief marketing officer, Henry Harris-Burland.

Able to deliver small parcels and packages weighing up to 10kg, including pizzas, a Starship robot can keep hot food hot, and chilled food chilled.

It can operate within a two-mile radius of its base. Its lithium-ion batteries require replenishing every three-to-four hours.

With all six of their wheels driven, the robots can tackle rough and uneven surfaces.

Harris-Burland admits to being surprised by how well the robots have blended into the cityscape.

“Most people ignore them although we’ve had one or two try to stroke them,” he says. “I suppose it’s because they look cute, friendly and non-threatening.”

What happens if somebody tries to steal one?

“Pick it up and a siren will go off,” he replies. “We’ve not had one stolen yet.”

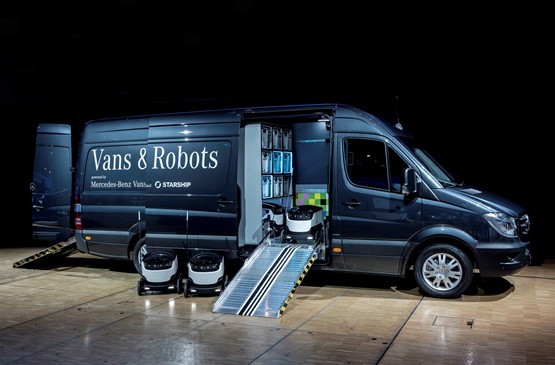

The delivery robots first attracted widespread attention at the 2016 IAA Hanover Commercial Vehicle Show in Germany when they appeared in Mercedes-Benz’s concept Vision Van.

An electric Sprinter-sized light commercial, it also featured a pair of drones mounted on its roof, the idea being that they could fly items ordered online direct to consumers.

“Our vans will become mother ships, with drones and robots swarming out,” said Volker Mornhinweg, global head of Mercedes-Benz Vans. Its parent company Daimler has become a key investor in Starship.

A slightly different approach has been trialled by Amazon. In it, the drone plays a role, but is not the final link in the delivery ‘chain’.

Amazon has been testing such deliveries under the Prime Air banner in the UK. Mercedes trialled them in Zurich, Switzerland, over 10 days last autumn in conjunction with US drone system developer Matternet and Swiss online marketplace siroop.

The trial was aimed at consumers who wanted items weighing no more than 2kg – the maximum payload of each of the two drones deployed – delivered the same day.

With a range of just more than 12 miles, a drone would be loaded at the distribution centre then flown to one of two Vito vans fitted with precision landing technology parked at one of four rendezvous points around the city.

The drone would come to rest on a platform on the vehicle roof 2m from the ground to avoid injury to passing pedestrians, says Mercedes.

The consignment was then unloaded by the van driver who covered the ‘last-mile’ by road to the waiting customer. Meanwhile, the drone flew back to the distribution warehouse to await the next consignment.

Why not fly the drone directly to the client? Surely this approach defeats the whole object of the exercise?

The difficulty is that city dwellers often live in flats. Piloting a drone onto a balcony (assuming they have one) is likely to be tricky and potentially hazardous, especially given the balcony is unlikely to be fitted with guidance equipment.

Flying the cargo to a van placed within striking distance of the customer’s home eliminates most of the journey from an out-of-town-hub through congested urban streets to get the item where it needs to go, Mercedes says.

Drone deliveries were made seven hours a day, but only in favourable flying conditions. Like all modes of transport, drones are vulnerable to bad weather.

Equipped with sense-and-avoid systems, the drones were equipped with parachutes that would deploy automatically if there was a malfunction.

With some 100 flights made without incident, Mercedes feels the exercise has been a success. “We’re extremely satisfied with the results,” says Mercedes-Benz Vans head of future transportation Stefan Maurer.

“The aim was to test the technology and the concept in real-world conditions and find out where optimisation was required. We also wanted to know how people would react to this new form of transport.”

The trial’s findings are now being analysed, he says.

“We’re convinced the project will evolve rapidly,” Maurer adds. “We see great potential for our solution and intend to expand it to include further areas of application.”

Mercedes says the Zurich exercise was the first time beyond-line-of-sight drones landing on light commercials have been flown extensively in a city and permission had to be sought from the Swiss Federal Office of Civil Aviation. Alternative modes of delivery, such as drones, can face legal restrictions.

Ocado points out that areas where testing of self-driving technology can take place have been defined by the UK Government. “You can’t simply turn up anywhere in the country and operate driverless vehicles,” says a spokesman.

One of the problems autonomous vans, robots and drones (if they are not deployed in conjunction with a van and driver) have in common is the need for the consumer to go out and collect the delivery from the devices when they arrive.

But what happens if the customer is elderly or disabled? They may not be able to leave the house.

It is a point recognised by Ocado which envisages CargoPod as an optional means of delivery. A van plus a driver who could carry goods into your home would remain available if that is what the customer required.

An alternative to a manned van could be a cyclist pedalling a cargo bike able to carry some 50kg. Courier CitySprint recently doubled the number of cargo bikes it runs in London to 22.

UPS has been trialling trailers towed by cyclists on parcel delivery work in Camden, north-west London. Able to carry around 200kg, the trailers are electrically-powered to lessen the burden on the cyclist. The parcels are delivered from a UPS depot to a local hub and loaded on to the trailers for their final journey.

A key advantage of all these mentioned means of delivery so far as Transport for London (TfL) and local authorities all over the country are concerned is they are zero-emission.

Determined to improve air quality and cut emissions of harmful pollutants such as NO2 – nitrogen dioxide – from vehicles, TfL will be orchestrating the introduction of an Ultra Low Emission Zone in April 2019.

Five CAZ cities

Birmingham, Derby, Leeds, Nottingham and Southampton are expected to introduce Clean Air Zones by the end of 2019 in line with the Government’s Air Quality Plan published last July and will be the first of 29 English local authorities expected to clean up their act.

Wales and Scotland are heading down the same path with Glasgow set to bring in a Low Emission Zone by the end of this year.

Returning to England, Oxford aims to bring in a Zero Emission Zone in 2020. Electric vehicles will be welcome – but diesel and petrol vehicles will be banned.

A key limitation of all the last-mile delivery solutions outlined here is the limited amount of weight they can carry compared with how much can be swallowed by a car-derived van, never mind the 3.5-tonners regularly deployed as home-delivery workhorses.

A growing number of 3.5-4.25-tonners are likely to be available in zero-emission electric guise over the next few years.

Their ranges should make them a viable option for fleets wishing to undertake last-mile deliveries from distribution centres on the edge of urban areas to city centre hubs for onward delivery, or direct to customers.

Electric versions of Iveco’s Daily and LDV’s Maxus are already available and an electric Renault Master is being introduced.

An electric Mercedes Vito is on its way, too, and battery-powered versions of Mercedes-Benz’s Sprinter and Volkswagen’s Crafter should arrive in 2019 and 2020/21 respectively.

Four left-hand-drive eCrafters have already arrived on this side of the Channel and are on trial with four different customers, says VW.

Electric versions of Citroën’s Berlingo, Peugeot’s Partner, Renault’s Kangoo and Nissan’s NV200 have been around for a while and the latter two models recently benefited from an upgrade.

Kangoo’s increased range

Kangoo Van ZE 33 has a 168-mile range between recharges, according to the outgoing official New European Driving Cycle (NEDC) figures.

That is 50% more than its predecessor thanks to the installation of a new lithium-nickel-manganese-cobalt battery with more energy density.

Nissan e-NV200’s up-rated battery gives it an NEDC range of 174 miles between recharges.

Such figures are, of course, optimistic. Renault admits as much and quotes estimated summer and winter ranges of 124 miles and 75 miles for the zero-emission Kangoo.

They show, nevertheless, that ranges are steadily lengthening.

Going electric is not the only zero-emission solution. CitySprint is testing a hydrogen-fuelled Renault Kangoo in London with a claimed 200-mile range. All you get when hydrogen reacts with oxygen is water.

Going the electric route means fleet operators face the challenge of how to recharge all their battery vehicles at the same time when they return to home depot after a day’s work.

Up until recently that has involved paying for a major upgrade to the local power network, but UPS has solved the problem by employing a different approach at its premises in central London.

It is ensuring it always has sufficient power to keep its vehicles charged up by deploying a bank of storage batteries and a so-called ‘smart grid’ which carefully manages the site’s electricity consumption.

As a result, it is now able to base 170 electric vehicles there rather than the previous 65. The plan for the future is to use second-life storage batteries that were previously used in a UPS delivery wagon.

The UPS scheme has been implemented with the support of the Smart Electric Urban Logistics project run in conjunction with the Cross River Partnership and UK Power Networks.

Funding was secured from the Office for Low Emission Vehicles.

Last-mile delivery encompasses the requirements of businesses as well as private householders. They, too, expect goods to be delivered in a timely, and hopefully environmentally-friendly, manner.

That is something recognised by Hovis.

With locations in Mitcham, Erith, Dagenham and Forest Gate on the fringes of London involved in baking and bread distribution, it has just acquired two electric Fuso eCanter 7.5-tonners.

Operated on two-year/unlimited mileage contracts, they are delivering in and around the capital.

The first battery-powered light truck to enter serious production, eCanter has also gone into service in London with DPD and Wincanton under the same type of agreement. The former has taken two, the latter, five.

Fuso is owned by Daimler and its products are sold and supported by the Mercedes-Benz truck network in the UK.

The eCanter offers a 62.5-mile range, says the manufacturer; more than enough to get from the outskirts of London to the centre and back.

Using a fast-charging system, the truck’s six lithium-ion batteries can be returned to 80% of their capacity from a 0% starting point in no more than an hour.

Two eCanters have been in service in Berlin with DHL Freight since last December on a two-year trial.

They are tackling regular 25-mile runs from the company’s Wustermark depot to the west of the German capital, into the city centre.

Loads typically consist of domestic appliances weighing more than 35kg which are delivered to private customers.

Moving up the weight scale, Renault Trucks and Volvo both plan to launch electric trucks in 2019. Renault has been trialling battery-powered 12- and 16-tonners with operators for the past decade.

Ten 18- and 25-tonne Mercedes eActros rigids have just gone on trial with fleets in Germany and Switzerland. Mercedes aims to put eActros into series production by 2021.

Battery-powered vans and trucks are far quieter than their diesel equivalents which makes night-time deliveries much more palatable; assuming businesses and consumers are happy to accept goods out-of-hours.

If they are, then any ancillary equipment fitted to vans and trucks has to be low-noise, too.

Last year’s John Connell Quiet Logistics award went to a partnership between Hiab and retailer Pets at Home.

It involves the use of Hiab electric truck-mounted forklifts to make evening deliveries to Pets at Home stores rather than the noisier diesel forklifts that were previously employed.

Extending delivery hours should help fulfil another of the ambitions of TfL and councils countrywide; achieving more efficient use of the road network thereby reducing traffic congestion during daylight hours.

Something else favoured by TfL is the use of urban consolidation centres; having goods destined for, say, several city centre retailers sent to one location close to the main shopping area then loaded onto a single truck for delivery.

A single truck going from one shop to the next is preferable to having a dozen run by different operators making separate deliveries to stores and clogging the highway.

Nor is that an approach that only benefits retail outlets.

A report produced in 2017 by the Independent Transport Commission highlighted the success of the DHL-managed London Boroughs Consolidation Centre, which organises deliveries to local authority sites.

Reducing restrictions on night-time deliveries is favoured by the London Assembly’s transport committee in a recent report, London Stalling.

It wants a switch away from flat-fee congestion charging to road pricing. The move would involve a fee structure dictating that drivers entering the capital’s centre when congestion is at its worst would pay the most.

Responding to the report, London Chamber of Commerce and Industry chief executive Colin Stanbridge says: “Our concern would be that businesses are not used as money-spinners and that any new scheme takes into account the economic value of a journey.

"Excessive charges imposed on delivery vehicles will end up being reflected in the prices customers will pay.”

jyoti sharma - 31/08/2018 07:17

The technology advancements have a greater role to play when it comes to any area of developmental changes. For more efficient work we need to keep apace with the technology.