The pace of change in just the last 10 years in the automotive sector has been enormous.

The pace of change in just the last 10 years in the automotive sector has been enormous.

It has included the accelerating transition to battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and the increasing use of connected technology, while global events such as the Covid-19 pandemic have turned many industry norms upside down.

But these are just an appetiser to what is to come in the next five years, predicts Kevin Gaskell (left), the former chief executive of BMW and Porsche GB, who is now a leading entrepreneur and investor.

“I would suggest that in the next five years, we’re going to see more change than we’ve probably seen in the past 50 and some of it is going to be pretty dramatic,” he says.

“There have been shifts and seismic changes in the past few years that none of us really expected.

“Nobody planned for the pandemic. Nobody planned for Russia invading Ukraine. And the impact on our sector has been pretty enormous.

"Everybody talks about semiconductors, but there is also supply issues over wiring looms, rare earth and precious metals, steel, aluminium and tyres.

“I was speaking to the CEO of a major manufacturer the other day, and he said it had to change its whole stocking policy from a two-day just-in-time to a 28-day just-in-case.

“I asked him if he could ever see his company going back to two-day just-in-time and he said no, he couldn’t imagine it. The impact of the world events on his company has been too enormous.”

Gaskell, who was speaking at the Belron Global Client Conference in Barcelona, says the disruption to global trade has caused an increase in protectionism and trade regulation.

In the UK, this has been supplemented by the uncertainty created by Brexit, which has led to numerous challenges in the supply chain, including highly volatile price changes, issues with raw materials and disrupted supply.

“It’s going to be very challenging for manufacturers to be stable and efficient in this new environment,” he says.

“Who knows what’s going to happen with global macroeconomics over the next three to five years?

"What I do know is it’s going to be disruptive. It’s not going to be easy for people to operate.”

Race for electrification

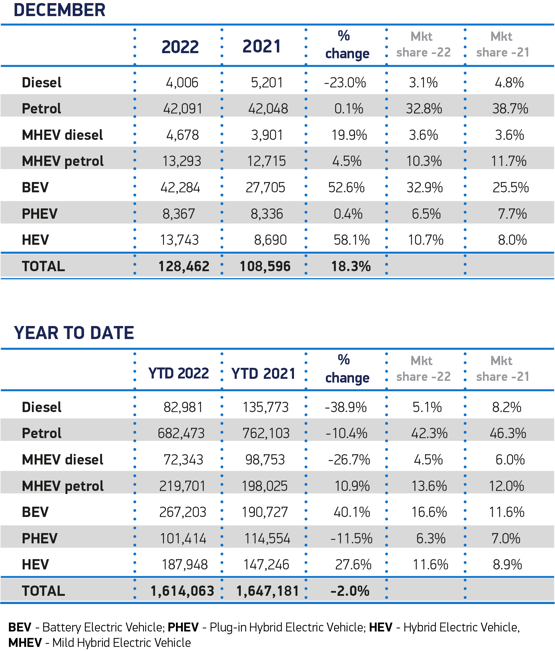

Electrification is top of many fleets’ agendas and their success – and the growing uptake by private buyers – is shown in the SMMT’s latest registration figures (above).

Despite supply issues and lengthy lead times, they show that last year, BEV registrations rose 40.1% compared to 2021.

They sat at 16.6% of the new car market, 5.0 percentage points higher than last year. In the UK, the adoption rate will also be accelerated by the Government’s ban on the sale of new conventional petrol or diesel cars and vans by 2030.

Globally, analysis by Bloomberg New Energy Finance predicts 30% of all new vehicle registrations globally will be BEVs by 2025, rising to 50% in 2030.

The transition poses challenges to both manufacturers and users, says Gaskell, including the enormous cost of the research and development required to produce a new form of vehicle.

“The cost of manufacture of the running gear, suspension and chassis is consistent whether it’s a BEV or an internal combustion engine car,” he adds.

“The big difference is the cost of the battery.

This is a real example from a well-known manufacturer with a well-known vehicle: the cost of the battery is six times the cost of an internal combustion engine.”

The price of EV battery cells has declined in recent years as production rose around the world.

US research firm E Source estimates they currently cost £107 per kWh on average, and by next year could drop to around $110.

However, E Source suggests the cost is primed to surge 22% from 2023 through to 2026, peaking at £92 per kWh before they resume a steady decline through to 2031, possibly down to £75 per kWh.

The projected spike is the result of growing demand for key raw materials, such as lithium, and supply not being enough to meet the growing demand.

This could drive up the price of BEVs sold in 2026 anywhere between £1,250 and £2,500, it says.

The greater cost of a BEV compared to an ICE vehicle presents manufacturers with the challenge of persuading customers to pay the extra for it.

“This is where you talk about brand management and brand positioning,” says Gaskell.

“The manufacturers have to move upmarket. They’re going to look for new niches. They’re going to look to get away from some of their history.

“You see this with Hyundai and its Genesis brand, and with Volvo and Polestar.

“Manufacturers are actually saying they’re going to go in a new direction, do things differently and mask price increases by bringing in a different product in a different place.”

The launch of an increasing number of BEVs by established premium manufacturers will also reshape the market.

“I frequently get asked what I think about Tesla,” says Gaskell. “What I would say is Tesla has kind of had the market to itself for six or eight years, but it hasn’t established that dominant position that means it owns the market.

“When you look at the market analysis, it’s interesting that in the sectors where premium manufacturers have launched competitive vehicles, Tesla has already lost 50% of its market share.

“I think it is going to have a tough time over the next few years.”

Helping the manufacturers control costs will be the fact that BEVs can use a new vehicle architecture – there is no need to have fixed positions for an engine, drivetrain or gearbox, for example – which means modular vehicles with easily exchanged components may become common.

This could mean BEV service and repair costs will remain the same or potentially lower than for ICE vehicles, says Gaskell.

A further benefit of modular construction could be that, by switching components, the vehicle’s use could change during its lifecycle.

“If you add to that the capability to upgrade the software, upgrade the drive technology, you’ve potentially got a vehicle that can go on and on, and be used for a long period of time,” he says.

“A number of manufacturers are talking about the million-mile car: a vehicle you use for this period of time may well become a utility, rather than a pride of ownership experience.”

This may mean the next generation of car users will move away from buying a vehicle to just using one, with subscription, usage and car-share models already growing as a percentage of the market.

Think differently

Manufacturers will also have to think differently about their business models, says Gaskell. The intellectual property of the vehicle operating system will become the key battleground, which is why so many are working to build their own operating systems, he adds.

For users, the main challenges will mainly revolve around the charging infrastructure, particularly if they live in cities and do not have off-street parking.

“When I walk through London, can I imagine streets of streets of vehicles with a cable running from a house, through a window and across the pavement?,” says Gaskell.

“It’s not a realistic consideration. So the limitation is going to be the charging infrastructure and whether that can be built quickly enough and it is convenient enough to encourage more people to change.”

As well as the rise of the BEV, another key automotive trend is the growing connected vehicle technology being found in cars and vans.

Much of this data, such as locations, driver behaviour and vehicle health, has the potential to aid a fleet decision-maker, but the flow of data between the vehicle, manufacturer and potentially the home and office will change the role of a technician, says Gaskell.

“A technician also has to become an expert on data management, data security and all the regulation around GDPR,” he adds.

“It becomes a sophisticated challenge and the role of the vehicle technician will change very substantially.”

The existing franchise dealer networks will also face major changes over the next five years, says Gaskell.

Some manufacturers, such as Mercedes-Benz and Jaguar Land Rover, have already announced plans to move from a traditional franchise network to an agency model.

This shift sees dealers left to focus on the customer interaction – handovers, servicing and used vehicle sales – while the OEM takes more control of the new car sales process, the customer data and the overarching customer relationship.

“The argument is this new system will increase the efficiency of stock management, but through conversations with my dealer community I think it’s going to be very challenging,” says Gaskell.

“It will transfer the ownership of the driver, as their relationship will be with the manufacturer and they will use that for their captive sales.

“They will be selling finance, insurance, service packages and everything else they can to retain that customer.

“Not every manufacturer has said they’re going to go this way, so it will be a real fight in the market about which of these systems work best.”

If a manufacturer moves to an agency model and keeps the vehicles on its own balance sheet, then the financial implications could be immense, says Gaskell.

“If you look at the balance sheet today for a financial services company compared to a manufacturer, that of the financial services company is a lot bigger,” he adds. “It needs a whole different level of funding and that is going to be tough for manufacturers.”

Humans in the driving seat

While Kevin Gaskell expects tremendous change in the next five years, the sight of self-driving cars becoming commonplace on UK roads will not be one of them.

“How long will it be before we get completely autonomous cars where I can put my feet on a dashboard, read the newspaper and be driven 100km down the road?” he asks.

“I don’t know, but I think it’s further away than people expect, I really do. “Consider the complexity of driving through a city: I drove through London yesterday and I certainly wouldn’t like to do it in an autonomous car.”

Before self-driving cars are able to be put into use on public roads, many insurance and legal issues need to be overcome.

The UK Law Commission has produced a report which recommends the manufacturer – and not the vehicle occupant – is responsible in circumstances such as when a vehicle is involved in an accident or goes over a red traffic light when it is driving itself.

“We all know that operating systems never have a bug, don’t we? Can you imagine? It’s one thing when your screen goes blue on a computer. It’s quite another when your car goes through a hedge!” says Gaskell.

“If there is an accident, and if it’s proven that something about the vehicle caused the accident, then where are the insurance companies going to look?

“Will they be looking at service centres and understanding whether the technicians were qualified. Were they certified? Did they have the appropriate training?

“It’s going to be a whole different ball game.”

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.